Tempo Manor History

Colonel Maguire & Lady Cathcart

No drowsy, eyelashed film-star with her dumbfounding bag of stale love-philtres had anything on the lovely Elizabeth Malyn as a connoisseur of husbands. Sir Richard Steele, the famous essayist, once met her on horseback at Enfield Chase. She impressed him so much with her “surpassing loveliness that he ever referred in enraptured terms to her charms of beauty, health, youth and modesty.”She began her trips to the altar at the more or less tender age of eighteen, urgently requested by distracted parents eager to have her settled. They had chosen James Fleet, the naïve son of the Lord Mayor of London in 1692. Her second husband, Colonel Sabine, a Governor of Gibraltar, had plenty of money. Her third, Lord Cathcart, commanded the greatest British fleet that ever sprang at heaven’s command from out the azure main, bound for the West Indies. Her fourth, Colonel Maguire, the only man she married for love, proved not only an autocrat at the breakfast-table the first day of her honeymoon, but a disaster. She wore a ring on her finger engraved with the couplet

“If I survive I will have had five”

Elizabeth survived, but did not marry again, although she stuck to the name Lady Cathcart. Hugh Maguire, the good-looking Irish laughing cavalier, had been too much even for her wide matrimonial experience.

Elizabeth survived, but did not marry again, although she stuck to the name Lady Cathcart. Hugh Maguire, the good-looking Irish laughing cavalier, had been too much even for her wide matrimonial experience.

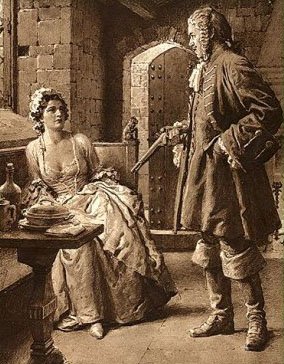

“What the devil do you mean, Hugh?” demanded the angry Lady Cathcart at their first breakfast alone at her home, Welwyn Manor. “Who gave you leave to pack my best silver and sell it to dealers in London?”

“I’m smothered in debt,” guffawed Colonel Maguire. “I need money. You won’t give me any. We’re married now, and what’s yours is mine. That’s the law, isn’t it? Where on earth have you hidden all those jewels you wore at the wedding yesterday? I searched your dressing-table while you lay asleep.”

Lady Cathcart made a gesture of impatience. “I’ll see you never lay a finger on my jewels, you-you-highwayman! That silver belonged to Lord Cathcart.”

She was still a strikingly handsome woman, every inch a well-preserved Lady, English to the backbone, very much alive and irresistible. Her eyes were wise and experienced. The only signs of age, which she tolerated with good grace, were fine wrinkles at the corners of her eyes, the result of ready smiles. Her head was well-poised and her carriage confident.

Colonel Hugh Maguire had seen many wars in Europe and had fought for Maria Theresa, Queen of Hungary. He made no secret of the fact that he had married Lady Cathcart for her money. Like Petruchio, in “The Taming of the Shrew,” he undertook to marry her practically before he had seen her, a purely commercial matrimonial adventurer. She had already bought him a Colonel’s commission in the British Army when he was on his way to the gutter. He had the sly look of the bully who thought he was getting away with some petty tyranny. He looked more dignified and impressive than clever, and was less vital than his wife, in spite of the smack and tang of his winning tongue.

“Nice way to begin a honeymoon,” Lady Cathcart went on bitterly. “You told me you had a big estate in Fermanagh. Why don’t you borrow on it?”

“I’ve tried, my dear,” laughed the hardened gallant, unperturbed. “Tempo’s ancestral halls are a liability, not an asset. How about raising me some money on this big house of yours? Where are the title-deeds?”

“Where you will never find them!” she snapped angrily, and left the table, her breakfast untouched.

Lady Cathcart spent a tearful morning in her bedroom. She knew there was no time to be lost. She locked her door, took off all her clothes, and sewed her more valuable jewels in the folds of her voluminous petticoats. She plaited more in her magnificent hair. The title-deeds to her house she hid even more carefully. Behind a heavy curtain was a concealed door. She put the title-deeds, wrapped in oiled paper, in an iron chest behind the door and fastened the key around her naked waist. Mortification at his ferocious disregard for her beauty and his preoccupation with her money nerved her to outwit this derisive, fortune-hunting Irishman.

Lady Cathcart spent a tearful morning in her bedroom. She knew there was no time to be lost. She locked her door, took off all her clothes, and sewed her more valuable jewels in the folds of her voluminous petticoats. She plaited more in her magnificent hair. The title-deeds to her house she hid even more carefully. Behind a heavy curtain was a concealed door. She put the title-deeds, wrapped in oiled paper, in an iron chest behind the door and fastened the key around her naked waist. Mortification at his ferocious disregard for her beauty and his preoccupation with her money nerved her to outwit this derisive, fortune-hunting Irishman.

He swaggered about Welwyn Manor as if he owned it. He was familiar with the maids. He drank, gambled, sang bawdy choruses with the stable boys one-day and beat them the next, much to their astonishment. He kept up a brisk sale of Lady Cathcart’s movable property, horses, silver, pictures, books. The dealers chuckled when he brought them her trousseau.

“If you’d only get me some real money with a mortgage on this castle,” he retorted when Lady Cathcart appealed to his honour, “I’d drop this tawdry hawking like a shot.”

“I’ll never do that,” she said. “I’m humiliated enough before the servants and neighbours. They all know what takes you to London so often.”

Maguire grinned broadly. “My attorney says it would be all quite simple. All he needs is your signature and your title-deeds. He’d lend me ten thousand pounds.”

“Clever man,” she scoffed. “Did he tell you how to pay it back? Have you no money?”

“Not a penny; never had. Where are those deeds, Elizabeth?”

“My attorney has them.”

“Liar! He says you have them here at Welwyn.”

“You saw him?”

“Yesterday. Wouldn’t lend me a penny and showed me the door, damn his yellow foxy face!”

Lady Cathcart looked at him thoughtfully and left the room, wondering what his next move would be.

One morning a week later the determined Colonel Maguire planned to kidnap his wife and take her to Ireland. “I’m taking you for a drive,” he said pleasantly, “to see an old friend. The coach and horses are ready at the front gates.”

When Lady Cathcart found the drive rather prolonged she asked suspiciously, “Where are we going? Take me home immediately.”

“You’re on the road to Holyhead,” he replied grimly, cracking his whip at the horses. “You’re going to Ireland. A stay at my Tempo Castle will bring you to your senses about those title-deeds. Chester’s the first stop. I’ve booked rooms at the White Lion Inn, where we’ll stay a night or two before taking the packet to Dublin.”

“You’re on the road to Holyhead,” he replied grimly, cracking his whip at the horses. “You’re going to Ireland. A stay at my Tempo Castle will bring you to your senses about those title-deeds. Chester’s the first stop. I’ve booked rooms at the White Lion Inn, where we’ll stay a night or two before taking the packet to Dublin.”

She tightened her lips and said nothing. She hoped something would happen at Chester to stop this mad journey. Lady Cathcart’s attorney had no illusions about Maguire. When he heard of her long absence in the coach, he immediately approached the Lord Chief Justice, explained the position and asked for a writ of habeas corpus. This was granted. The attorney sent a messenger to Chester hoping to detain lady Cathcart in England. Unfortunately, the messenger did not know her by sight. The crafty Maguire had got wind of the plot to hold his wife, and bribed a woman of the streets to impersonate Lady Cathcart at the White Lion Inn.

“I’m going to Ireland with my husband of my own free will,” this woman haughtily told the puzzled messenger. “I resent his interference. Go back to Welwyn and tell my friends I am quite all right.”

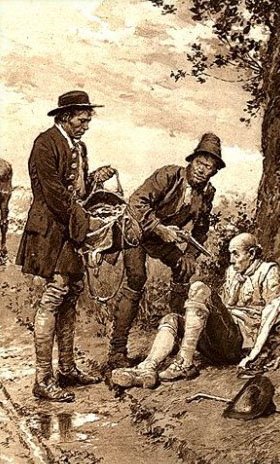

Maguire was thorough. He further bribed two highwaymen to beat and rob the messenger of the writ and all his papers. This job they carried out efficiently, handing Maguire the writ to hold Lady Cathcart.

Maguire was thorough. He further bribed two highwaymen to beat and rob the messenger of the writ and all his papers. This job they carried out efficiently, handing Maguire the writ to hold Lady Cathcart.

They soon crossed the Irish Sea, and a few days later she was a prisoner in a wild, rambling Ulster castle, Maguire’s home at Tempo, County Fermanagh. He told his ignorant Irish servants, “She’s not quite right in the head, and has come to Tempo for a rest. Don’t try to see her or she’ll do you an injury.” The superstitious servants fervently crossed themselves and avoided her locked room like the plague. Maguire, her husband turned jailer, brought every meal and held a pistol to her head if she showed signs of making a disturbance.

“Tell me where your title-deeds and jewels are and you’ll be back at Welwyn in a week,” was his daily slogan to her.

Lady Cathcart remained silent. The key of the hidden door behind the arras still lay safely round her waist.

Maguire gave a dance at his castle to celebrate his wedding and homecoming. In a speech to his guests he regretted: “My wife is as yet too ill to be with us. We’ll drink her health and I’ll send a servant to tell her of our best wishes for a quick recovery.”

Lady Cathcart ‘s health was drunk; the servant departed, to return in a few minutes with the lying message: “Thank you all very much. I hope you are enjoying yourselves with my dear husband.”

Of course, there was whispering and talk at the non-appearance of Lady Cathcart. The countryside knew Maguire too well. But talk was dangerous as the gallant colonel was a dead shot with the pistol and in those days duels were common on the least provocation, even in Ireland.

One man was called out because of a disparaging remark to Maguire about Lady Cathcart’s eyesight and mental state, “pickin’ a waster like you for a husband.” Maguire owed him money. With a sardonic sense of humour the colonel named the meeting place, five o’clock in the morning in the middle of a newly ploughed field on his estate. His opponent had fought at Culloden against Bonnie Prince Charlie and had lost a leg, which had been replaced with an indifferent wooden substitute. Long before he could reach Maguire standing in the middle of the ploughed field with his second, his leg got hopelessly bogged at every step and the colonel amused himself by firing balls over the afflicted man’s head.

During this time Maguire had tried everything to persuade his wife to give up her deeds and jewels, but she held tenaciously to her secret, although now a shadow of her former self. Confinement and want of fresh air was beginning to tell on her health and spirits.

Nobody knows how he managed to induce Lady Cathcart to give up her secret, but one-day he fled from Tempo in a hurry. He travelled to England by way of Donaghadee in County Down to Portpatrick in Scotland, as the sea journey was shorter and safer.

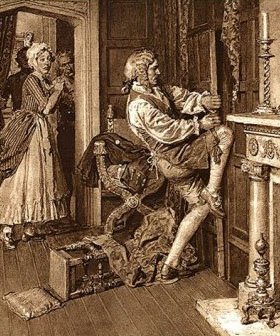

He arrived at Welwyn Manor in a state of uncontrollable excitement. Brushing away the queries of the eager servants, he rushed upstairs, three at a time, to Lady Cathcart’s bedroom, key in hand.

He arrived at Welwyn Manor in a state of uncontrollable excitement. Brushing away the queries of the eager servants, he rushed upstairs, three at a time, to Lady Cathcart’s bedroom, key in hand.

He tore away the hangings and pressed the wooden panel. The door only moved a few inches. Plucking a great jack-knife from his pocket he hacked the old oak and clawed at the door with shaking hands. It was useless. With sweat on his brow he renewed his frantic efforts. The servants tried to dissuade him, but he drove them from the room with curses.

The knife slipped and cut a great gash in the thumb. Lockjaw set in and Colonel Maguire died as his ambition was almost realised.

Lady Cathcart was soon released when news of Maguire’s death reached Tempo. Her attorney made no mistake this time, travelled to Ireland, and brought her back to Welwyn.

She was lively to the last, danced a minuet when she was eighty, and lived till her ninety-fifth year, a life full of charity and good works.